Vectors Fundamentals#

scalar: A quantity described purely by a number.

e.g. \(1.1, 2, 3\ldots\); one tree; 3 spacecraft; 7 robot arms.

In dynamics, you will also see scalars in the context of quantifying masses (e.g., the mass of a professional football is \(430\) g, which is a scalar unit of measure) or geometric dimensions (e.g., the circumference of a professional football is \(63.5\) mm, which is also a scalar).vector: a quantity characterised by both magnitude and direction.

Notation of Vectors: handwritten and typewritten#

Vectors are commonly denoted using letters from the English and Greek alphabets. When typed, you will typically see a general vector typed in boldface. For example, \(\bf a\) is a vector. When written by hand, you will see instructors use two common notifications. Below, we show how the vectors \(\boldsymbol\alpha\) and \(\bf a\) are commonly written by hand.

In live lectures by Angadh, you will commonly see the highlighted notation in his handwriting. However, both notations are equally valid.

Graphical Representation of Vectors#

Vectors are drawn as a directed line segment (i.e., a line segment with an arrow at one end).

They are typically represented for two cases:

Conversely, by the same rule, a clockwise vector will have a negative direction and points into the plane of the paper.

Attention

The inclination of clockwise and counterclockwise vectors is \(90^{\circ{}}\) with respect to the plane of the paper or the computer screen.

Unit vector#

A vector of unit magnitude (i.e., its magnitude is \(1\)).

Unit vectors are commonly written with a caret \((\hat{\ })\); this is typically seen over a letter in the alphabet. For example, \(\hat{\bf i}\) is a unit vector and \(\left|\hat{\bf i}\right|=1\) says that magnitude of \(\hat{\bf i}\) is \(1\).

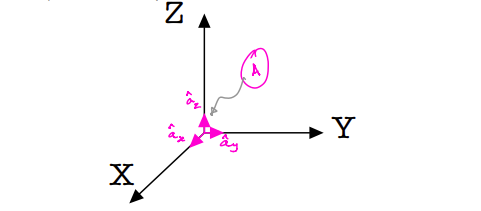

Reference frames#

A set of three right-handed unit vectors (i.e., obeying the ‘right-hand rule’) that are mutually orthogonal.

In Fig. 1 below, \(X-Y-Z\) form a Cartesian coordinate system. \(\hat{\bf i},\;\hat{\bf j}\;\& \;\hat{\bf k}\) (drawn in pink) are a set of unit vectors that are mutually orthogonal and directed along \(X\),\(Y\), and \(Z\), respectively.

Fig. 1 Reference Frame R and its unit vectors.#

The set of unit vectors are right-handed (also known as a “dextral set”), which means the following relationships hold true:

In reference to Fig. 1 above, this set of unit vectors forms a reference frame \(R\). Reference frames are useful for studying moving objects. This is discussed in further detail much further on in this book.

Other notations of unit vectors

An alternate notation for unit vectors that make up a reference frame commonly used for dynamics is shown in the figure below; it makes use of subscripts in \(x\), \(y\), and \(z\) to make explicit along which coordinate axis the unit vectors are aligned. We will (almost always) see (and use) this alternative subscript-based notations in dynamics for sake of clarity.

Fig. 2 Reference Frame A and its unit vectors.#

\(\hat{\bf a}_x\) is the unit vector along the \(X\)-direction

\(\hat{\bf a}_y\) is the unit vector along the \(Y\)-direction

\(\hat{\bf a}_z\) is the unit vector along the \(Z\)-direction

This is a right-handed set of unit vectors. In the Fig. 2 above, this set forms the reference frame \(A\).

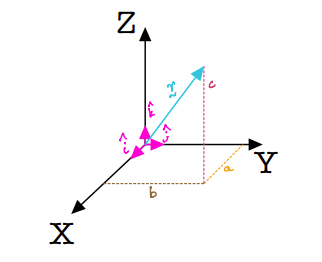

Component form#

Let \(a,\;b,\;c\) be three scalar coordinates that describe the location of an arbitrary point in space in the \(X-Y-Z\) coordinate system as shown in Fig. 3. We can locate this point from the origin of the using a position vector, denoted as \(\bf{r}\). From our earlier review on vectors form the videos, we can see (in Fig. 3) that the tail of the vector is at the origin while its head is at the point of interest.

Fig. 3 The scalar components of \({\bf r}\).#

Note

\(a,\;b,\;c\) are scalars and \({\bf r}\) is a vector.

The component form of this position vector, \(\bf{r}\), can be written as:

The above “component form” of expressing vectors makes use of scalar coordinates and their corresponding directions through the use of the unit vectors. In other words, the equation above says that we can march \(a\) units along \(X\), \(b\) units along \(Y\), and \(c\) units along \(Z\) to get to the head of the vector \(\bf r\).

Vector algebra using a CAS (Computer Algebra Systems)#

Attention

If you haven’t already done so, it would benefit the reader to review addition and multiplication of vectors from the video links on the preceding page on fundamentals.

In this book, we exploit a computer algebra system (CAS, for short) to perform vector algebra operations. A CAS is a software that allows manipulation of non-numerical as well as numerical mathematical expressions in a manner similar to that preformed manually (on a piece of paper by humans).

SymPy is an open-source and free CAS that we will use in our studies on dynamics in this textbook. It has many advanced features that are particularly useful in studying dynamics of rigid bodies.