JN1: Vector Algebra with a Computer Algebra System#

How to interact with this tutorial#

Warning

This portion of the discussion assumes you have access to the Jupyter platform. Two ways to access:

Recommended option: online access as provided by universities e.g., QMUL offers one to its students; or

Advanced and adventurous option: by installing Anaconda on your personal computer and accessing the Jupyter notebook interface. Instructions on using Jupyter notebooks with Anaconda can be found here.

This interactive Jupyter notebook is to help get you started using SymPy for performing vector computations. This contrasts with your standard hand-held calculator, which performs computations on scalar quantities.

This particular page is a Jupyter notebook-based tutorial that also contains a set of interactive exercises to gradually help get you started with the basics of computational vector algebra (which you now know how to do if you watched the videos here) using SymPy.

This textbook has more such interactive notebooks as well as other resources. Work through them at your own pace each week. I hope this makes learning to program a more enjoyable process.

Execute a code cell (such as the one right below) by clicking on it and simultaneously pressing ‘Shift+Enter’. You will then see a new line appear, which says My name is Bond. James Bond. You may change the text stored in name to your name.

name = 'Bond. James Bond.'

print('My name is ', name)

My name is Bond. James Bond.

Reference Frames and Vectors in SymPy#

In the preceding discussions, we reviewed vectors and reference frames. Therein, the component form of representing a vector was presented- this allows us to write a vector using its scalar components and some unit vectors.

For example: \({\bf v}= v_1 \hat{\bf{a}}_x + v_2 \hat{\bf{a}}_y + v_3 \hat{\bf{a}}_z\) is the representation of a vector \({\bf v}\) using the scalars \(v_i\) \((i=1,2,3)\) and a set of unit vectors \(\hat{\bf{a}}_j\) \((j=x,y,z)\). The set of unit vectors are called a reference frame, which we shall call \(A\), for the sake of this notebook- here, we also assume that these vectors have the special property of being orthogonal.

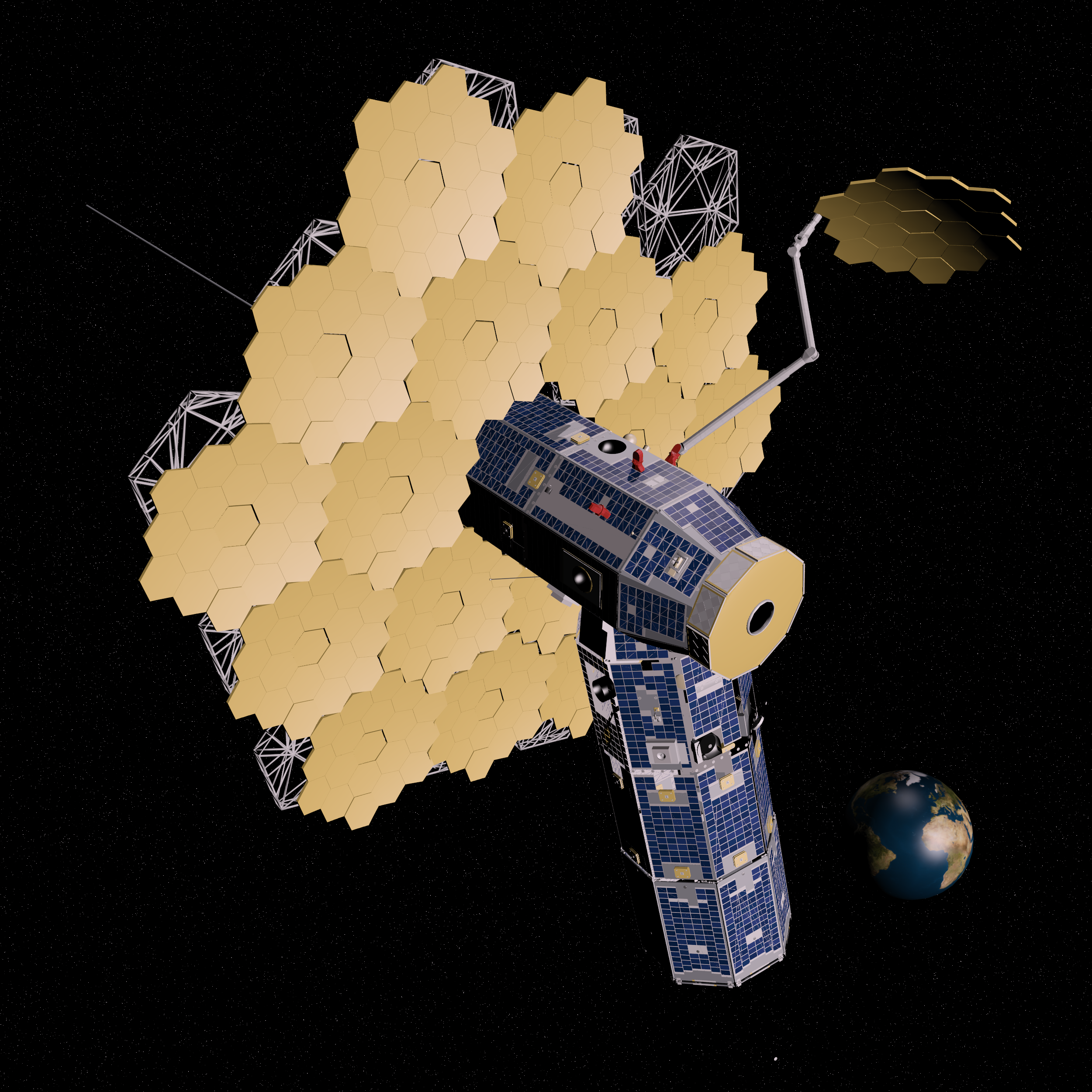

Engineering dynamicists utilize their understanding of vectors to generate models that describe the motion of engineering systems. Some exciting and important examples of systems analysed using dynamics models are rockets, spacecraft, aircraft, drones, etc. As these systems are quite complex, dynamicists have developed tools that facilitate their modeling. Another important aspect of a dynamicist’s work is in the analyses of motion behaviours using these models. This also helps in exploring aspects of the design space to improve the performance of machines (e.g., robots) or aid in understanding anomalies and failures in engineering systems.

The objective of this notebook is to introduce you to some fundamental tools that facilitate such complex mathematical modeling of systems using computers. To do so, we will use a computer’s ability to perform algebra (woking with symbols)- this is enabled by a symbolic library known as SymPy, which is written in Python. Here, we will learn not only to express a vector in its symbolic form but also to perform routine vector algebra operations (addition and multiplication) in SymPy. This will allow us to eventually develop a model that describes the motion of a spacecraft orbiting the Earth.

Initial setup: get the necessary tools!#

As with most programming languages, the first few lines are dedicated to importing tools that allow us to achieve this notebook’s objective.

For this, we will use SymPy’s symbols and ReferenceFrame.

from sympy import symbols

from sympy.physics.mechanics import ReferenceFrame

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ModuleNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[2], line 1

----> 1 from sympy import symbols

2 from sympy.physics.mechanics import ReferenceFrame

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'sympy'

Create the vector ‘v’#

We will first create the scalar components of the vector \(\bf v\), i.e.,

\(v_i\) \((i=1,2,3)\). It is good practice to declare symbols as real to

encourage SymPy to provide simpler results- this is why we have included

real=True.

v1, v2, v3 = symbols('v1, v2, v3', real=True)

Then, we create a reference frame- this provides the orthogonal unit vectors for constructing general vectors such as \(\bf v\).

A = ReferenceFrame('A')

The three orthonormal vectors (orthogonal unit vectors) associated with this

frame \(A\) can be accessed by appending either .x, .y, or .z to it. Let us

examine each of these.

A.x

A.y

A.z

Now, we can construct the vector \(\bf v\) by multiplying its scalars by the

frame’s

associated unit vectors. This vector will be stored, as shown below, in the

variable

v.

v = v1*A.x + v2*A.y + v3*A.z

The vectors stored in variable v can be displayed:

v

Now, a little bit of Python and computer programming terminology.

v and A appear to the left hand side of = in the code snippets above,

which

attaches these two letters to a Vector or a ReferenceFrame. In other words,

v and A are containers that store something. In computing, such containers

are

typically referred to as variables.

If we are unsure of or wish to learn what kind (or type) of object a variable holds, Python allows us to request this (and other) details by using a question mark, as below:

v?

The first line of the newly opened window tells us that v is a Vector. This is cool because we have just used symbols and ReferenceFrame to write a vector in its component form using abstract symbols and not numbers!

You may now close thenewly opened window in the bottom half of your browser.

Some operations on vector ‘v’#

As we are aware, vectors have some important properties. One of these is its

magnitude and SymPy allows us to access this information easily.

The scalar magnitude of v can be found by:

v.magnitude()

A unit vector in the same direction as \(\mathbf{v}\) can also be found with:

v.normalize()

which is equivalent to:

v / v.magnitude()

Vector algebra#

Addition#

To add a new vector, \({\bf w}= w_1 \hat{\bf{a}}_x + w_2 \hat{\bf{a}}_y + w_3 \hat{\bf{a}}_z\), to the vector \({\bf v}\) that we created above, we have to do the following steps:

w1, w2, w3 = symbols("w1, w2, w3", real=True)

w = w1*A.x + w2*A.y + w3 * A.z

w

Then, the two vectors can be added:

v + w

Reinforcement Activities#

Question 1: Can you write one line of code to add \(\bf v\) to itself?

# Enter your code below

Question 2: Can you create a new vector \(\bf u\) expressed in a new reference frame \(B\)?

# Enter your code below

Question 3: What is the result of adding \(\bf u\) to \(\bf v\)? Does this make sense?

# Enter your code below

Multiplication#

It is quite straightforward to multiply a vector by a scalar. For example:

Scalar product#

10 * v

Dot product#

Compute the dot product between two vectors:

v.dot(v)

Cross product#

Similarly, one can also take the cross products between two vectors:

v.cross(v)

Activity:#

Can you write code to compute the dot and cross products product between \(\bf v\) and \(\bf w\)?

# Enter your code below

v.cross(w)

Additional useful features#

The matrix form of both vectors and dyadics can be found if the frame of interest is provided.

v.to_matrix(A)

You can also find all of the scalar variables present in a vector with the free_symbols() feature, as shown below:

v.free_symbols(A)

Partial derivatives of vectors can be computed in the specified reference frame.

v.diff(v2, A)

You can substitute numerical values for scalar expressions.

v.subs({v1: 1.34, v2: 5})

Note that this does not alter the original definition of vector \(\bf v\) (or, more specifically, its scalars); this can be seen as shown below:

v

v1

v2

The above three code cells demonstrate that the original vector is unchanged. However, we can make use of the new substitutions by creating a new variable z and assigning it the numerical representation of the vector \(\bf v\) (stored in the variablev). This is shown below:

z = v.subs({v1: 1.34, v2: 5})

z.subs({5: v2})

Reinforcement Activity#

Run the following code snippet:

m = v.to_matrix(A)

m.subs({v1: 5})

Now, probe what type of object m. In other words, enter m? in the code cell

below and identify what its Type says:

#Enter your code below